From 2011 to 2015, Edward Mullany released a trilogy of books with Publishing Genius that I return to often. Tiny poems and microfables that are haunting, surreal, hilarious, and strange. He ended these three books with a trio of novellas (The Three Sunrises), a series of fever dream tales blending paranoia with confused narratives for a truly memorable reading experience.

To read Edward Mullany is to read something fresh and new. While you might be tired in a cubicle, before you know it, you’ll be right along with Mullany, climbing a ladder to the sky.

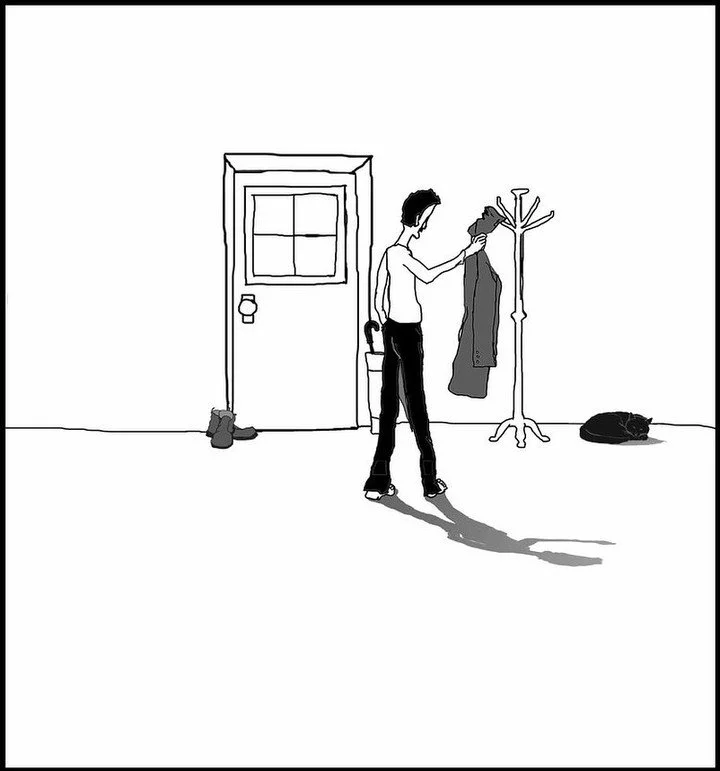

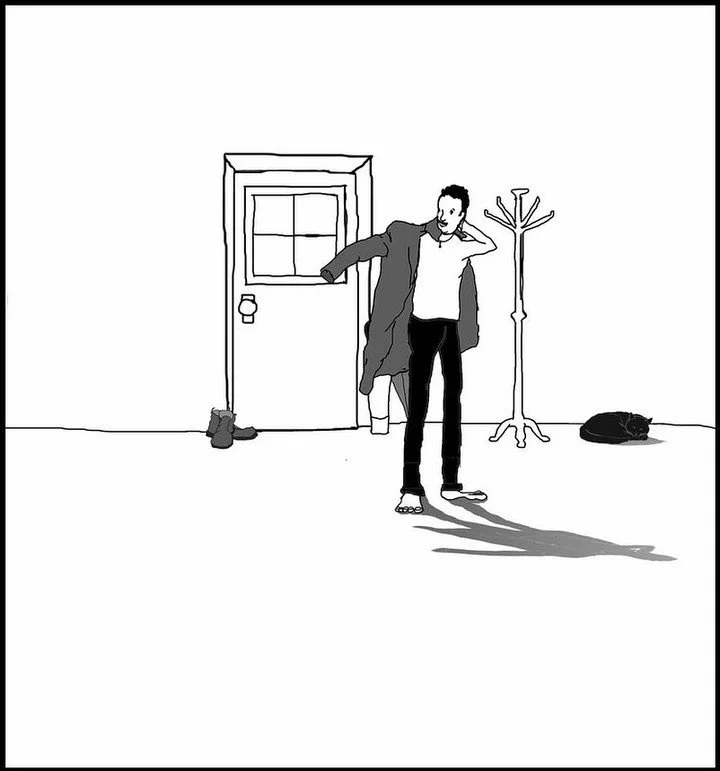

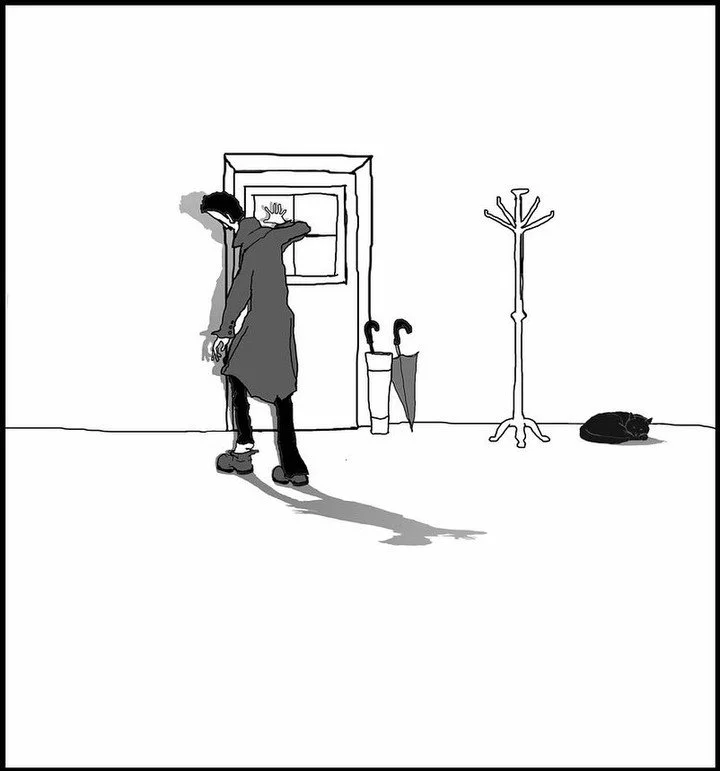

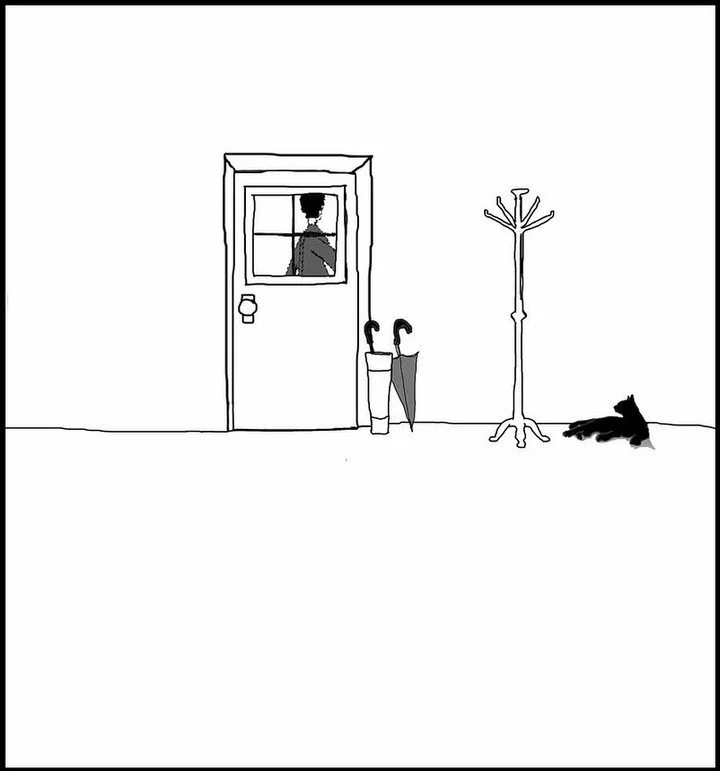

Now, ten years later, Mullany is back with his newest collection, Whiskey for the Holy Ghost. Featuring one-page tales alongside his own illustrations, the result throws us (comfortably and extraordinarily) right back into his world, where stories feel like dreams, where fictions are often one sentence long, and where anything is possible.

I chatted with Mullany via email about his four books, his near-daily art practice, his mixture of image and text, his classification of genre, and much more.

Congrats on your latest book! Can you talk a bit about the process of creating and assembling this book?

It's a collection of stories that were written mostly in 2018. The manuscript contained twice as many pieces in it, but I slimmed it down at the prompting of Adam Robinson, the publisher, when he and I began talking about it last year. I remember Adam saying something about the 'law of diminishing returns,' when we were discussing the efficacy of books whose style is somewhat recursive, as this one is. And so we cut it to what we hoped was a length wherein the freshness would not be lost, and arranged it into sections.

Whiskey for the Holy Ghost is largely made up of one sentence, one page paragraphs. Stories, flash, meditations, reflections, dreams. How do you describe these pieces / how do you describe this book?

I consider them stories, though I don't think it matters how one describes them. In their economy they could be said to share something with poetry, for example. But I'm not concerned with what they are, in terms of genre, as I write them. Their brevity is merely the natural end of their expression. Meaning, the length of each piece is determined by the piece's necessity; the writer is as generous as possible within the constraints that the story permits itself. He listens to what the story is telling him, and transcribes it, and doesn't add anything more.

This is your first book in ten years, with your previous books being part of a cohesive trilogy. How do you see this fourth release next to your other three? Do they feel in conversation with one another or something entirely different?

They're probably in conversation to some extent, as they are all written by the same author, and no author rids themself entirely of the themes and preoccupations that belong to them, and of which they aren't entirely conscious. But certainly this book feels different to me in terms of its subject, or plot. It isn't as foreboding as those first three books, and is even in some instances happy. It is also perhaps more ordinary, in terms of what it is 'about'. There is a category of art to which I think I'm trying to attain, wherein much of the 'drama' that an audience might expect to discover is extinguished by a kind of nothingness that is nevertheless edifying.

Can you reflect a bit on the trilogy you released between 2011 and 2015? You really hit the ground running with these three books. Did you always see them as a trilogy? How long were you working on these books and writing prior to that initial 2011 publication?

They were maybe a trilogy only in retrospect, and because of a thematic consistency that was going to be there anyway, in one way or another, because I wrote them proximate to each other, in time, and so was inhabiting some singular 'headspace' and mood. For example, the red-white-and-black color scheme that is evident in the cover art of all three books was chosen purposely, to tie them together, but I don't think I anticipated doing so until I'd completed the second book, Figures for an Apocalypse, and began to try to immerse myself in a vision that would give me direction and identity in what I suppose you could call the 'vocation' that is art. There is, as well, something like a moral or existential panic in those first three books that I don't think is evident in what I am writing now. Or anyway is not evident to such an extent. There is a calm at the center of these newer stories that does not betoken a world of such dementedness and nightmare.

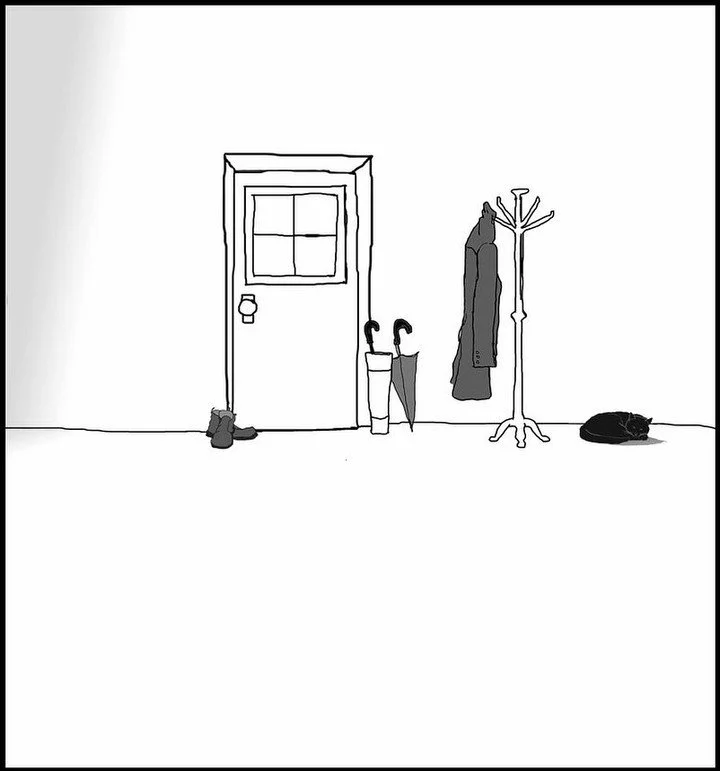

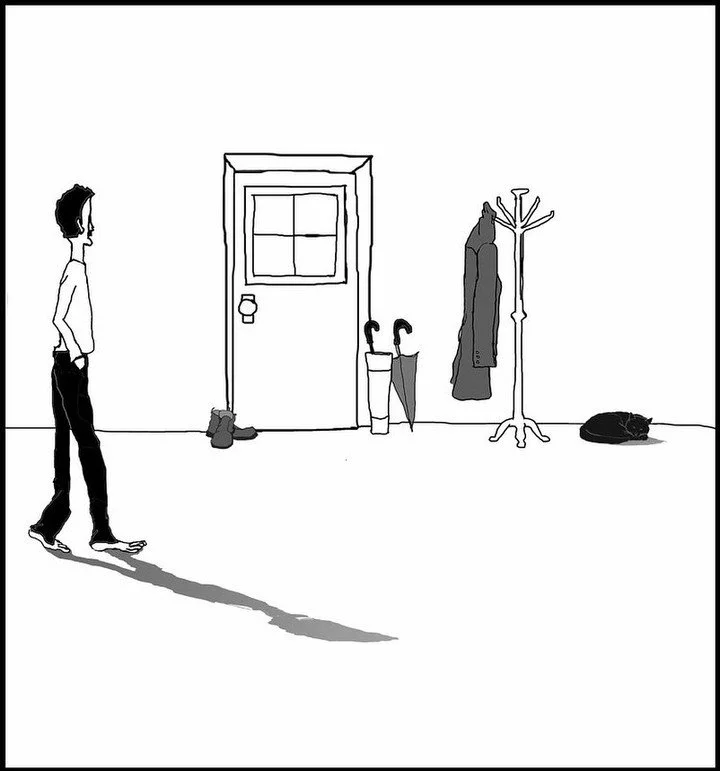

Your latest book also incorporates a number of your own illustrations. Image and text: does one arrive before the other, or do they overlap with one another?

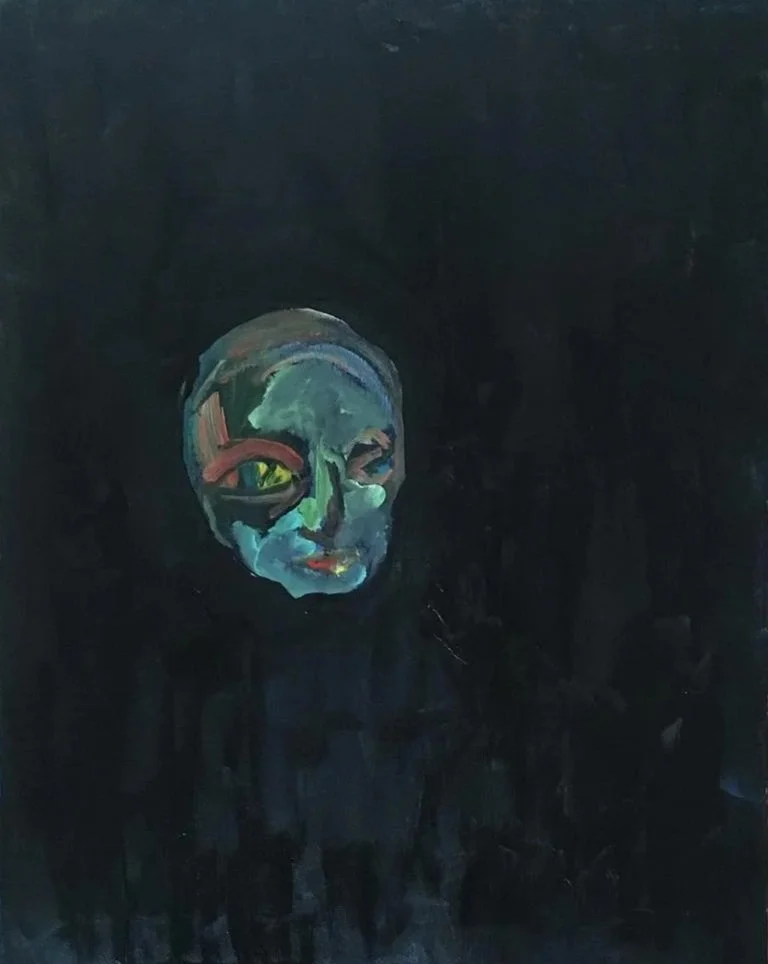

There weren't going to be any illustrations until a friend of mine, John Dermot Woods, made the suggestion. This was back when the manuscript was longer than it is now, with more stories in it, ones that Adam and I decided not to include. So the illustrations arrived as something like an afterthought. I worked on a handful of them every day for about a month. Many of them have a frenetic and unfinished quality that I didn't mind them having, because I didn't want them to correlate too neatly with the stories themselves, I didn't want them to be reductive. Even if, on the other hand, some of them may look elementary and unrealized.

With that in mind, how do you divide time between visual art and writing? Does one take up more of your free time than the other?

I swing back and forth between them, over the course of several months, like a pendulum, though I don't feel any difference inside myself, during the work itself, and take up only whatever project is speaking to me most insistently in the moment. Meaning, the drawing and the writing are two different instruments put to use for the same end, by the same person. Though it's true that afterward I sometimes prefer one project to another, or have a fondness for one that I do not feel for another. For example, I have a personal antipathy for City of Dis, which is a graphic novel I've been working on the last couple years, because it inhabits the strange spiritual darkness that I've been trying to abandon as a subject, or aesthetic, and had thought I'd put behind me; and yet I still feel compelled to attend to it, and that to ignore it completely would be an insult to my consciousness. You work in the times into which you are born, and those times give you your subjects, whether you want them to or not. And you feel a pang against your integrity if you don't heed them.

You've drawn a number of comics / graphic novels over the years, from drawings of mothers to a 'Calendar of Saints' to a daily illustration practice. Some you've shared in their entirety on your Instagram. Do you see these as year-long projects or something different?

I'm not sure how I see them, really, outside of what they are intended to be, and as efforts at creating art. The Calendar of Saints was a labor of love in the sense that I'm not sure it will ever be published, though I would like for it to be, and also in the sense that I now feel an increased friendship for, or devotion to, all those holy persons that I concerned myself with during the year that I worked on it to the exclusion of anything else. The drawings of mothers that I've been working on most recently I also feel partial to, because they originate in an area of my personality that wants to depict only scenes of tenderness, protectiveness, love, vulnerability, and creativity, as opposed to, say, violence and tension, or suspense. They verge on the sentimental, I'm sure, but that is ok with me. It's important for art to get as close to the sentimental as possible without yielding to it. And even if it does happen to yield to it, so what? By which I mean, I guess, oh well.

What are some touchstone books (or touchstone authors) that have captivated you and helped you in your writing career and/or your art process?

There are so many that have helped me, but if I had to name a handful I would say the Holy Bible, Moby-Dick, The Brothers Karamazov, the poems of Emily Dickinson, all of Flannery O'Connor, and the novels of Philip K. Dick. I list these not so much for what they've taught me about style, even if they have done that as well, but because they have articulated for me a vision of reality that I think is full of clarity and truth, yet not absent of mystery.

Although your latest collection is still very much in its infancy, have you written anything since? Are there other works in progress?

Yes, I've been trying for the last five years to write a non-fiction, diaristic book that is difficult to describe. I would say that, stylistically, it is inspired by works like 300 Arguments, by Sarah Manguso, The Book of Disquiet, by Fernando Pessoa, LIVEBLOG by Megan Boyle, and Pascal's Pensées. It began as an attempt to write a book about 'Our Lady,' which is a Catholic sobriquet for the Blessed Virgin Mary, and evolved into something else, something broader and more disparate, though not without that theological origin. I still want to write that same book, and am in the process of figuring out how.

Outside of your own work, what are some recent reads that you have enjoyed?

An amazing work of fiction I've been reading is the seven-part novel On the Calculation of Volume, by the Danish writer Solvej Balle. Only the first three books have been published so far in English, the fourth is expected next April. It is about a woman who keeps waking up in the day of November 18.

I'll ask the same question, but in regards to recent movies and/or music. What are some recently watched films or recently listened to albums that you'd recommend?

Two movies I recently watched are Ari Aster's Eddington, and the movie Tár, which was written and directed by Todd Field. I don't really love Ari Aster's movies, but I find them interesting, and I haven't seen a better depiction of what occurred during the height of the 'Covid' years, here in the United States, than what he portrayed in that movie. I thought Tár was impressive, the work of a great artist, one who is cognizant of truth and beauty and morality.

If you can, provide a photo of your writing workspace (or describe with words). What are some essentials while you create?

For this ongoing author interview series, I'm asking for everyone to present a writing prompt. It can be as abstract or as concrete as you choose.

Begin a sentence without any notion of how it is going to end.

In closing, do you have any advice for early writers or visual artists? Or rather, what's something that keeps you returning to your preferred mediums?

Don't be afraid to fail, and don't be embarrassed of the things you love, even if they aren't fashionable.