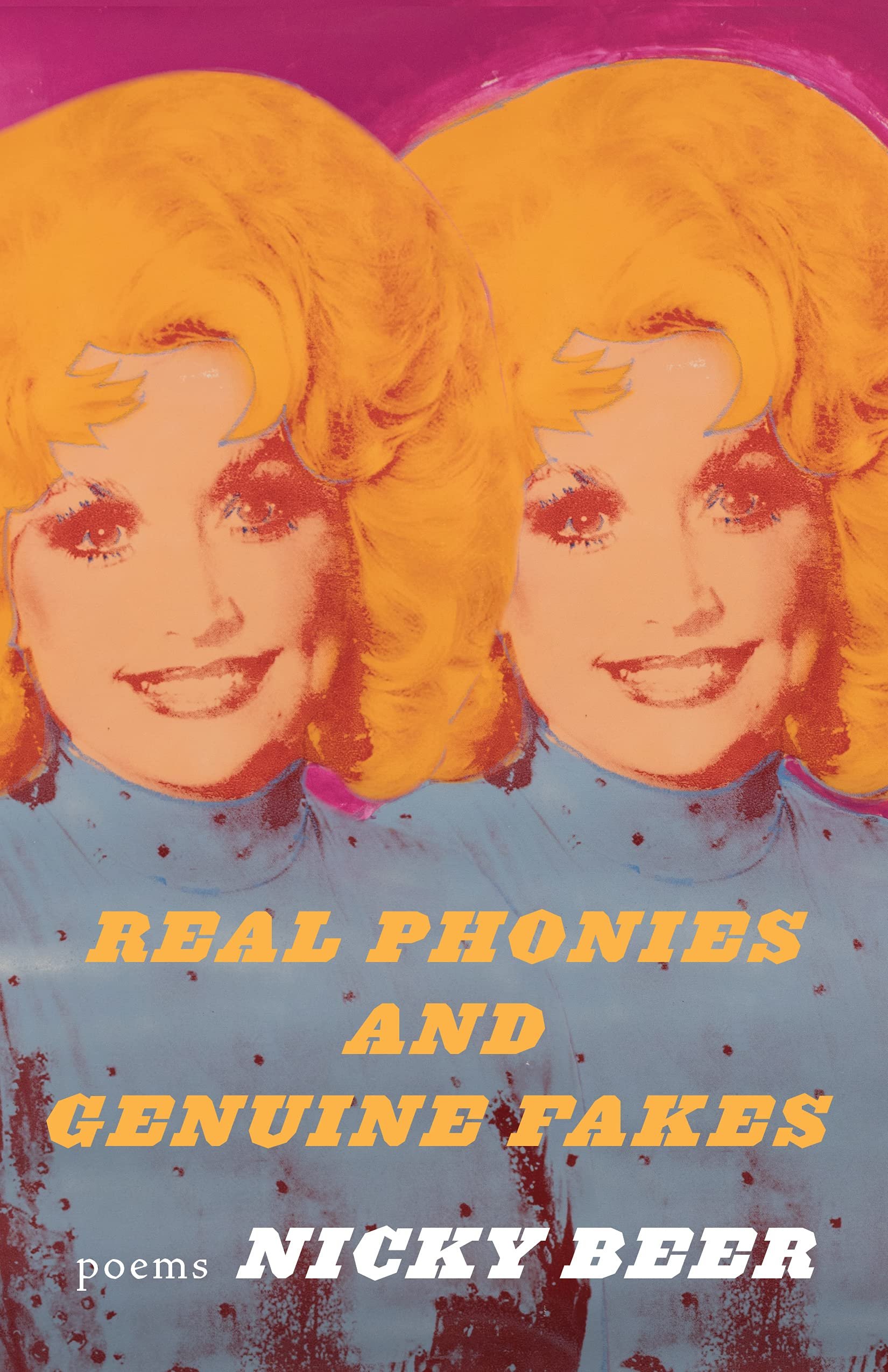

Writer, editor, and educator Nicky Beer is the author of three collections of poetry: The Diminishing House (Carnegie Mellon, 2010), The Octopus Game (Carnegie Mellon, 2015), and, most recently, Real Phonies and Genuine Fakes (Milkweed Editions, 2022). She is an associate professor at the University of Colorado Denver and the poetry editor for the journal Copper Nickel.

Inspired by the world around her, and with a sharp vocabulary of intellect and humor and wit, Beer’s writing seems to come from a place of sincere curiosity and continued obsessions. From cephalopods to stereoscopes to pop culture and beyond, her poems toe the line between science fiction’s absurdities and the tenderness of a prayer. That is to say: poetry that is difficult to classify and poetry that is masterfully done. In The Octopus Game, for example, she writes, “I want to shrug out of the year, hang it on a branch like a truant, and float out into the deepest part of this hour, forgetful as a fish.”

I chatted with Beer via e-mail and talked about surrealism, magic, trauma, memoir essays, cassette tapes from high school, and much more.

As an icebreaker: find the stack or pile of books/stuff nearest you. What book/object/item is at the very bottom of said stack?

A lovely note from the massively talented poet and letterpress printer Lindsay Lusby, who I commissioned to make a broadside of my poem “Because my grief was a tree” from Real Phonies and Genuine Fakes. As you can see, the results are beautiful!

Congrats on your new book! Can you talk a bit about its inception/process/concept?

Thank you! Real Phonies is my third book of poems, and just as there were challenges in figuring out how to move from a first book of poems to a second, so too were there challenges in moving from a second to a third. Particularly daunting was the fact that my second book, The Octopus Game, was an extremely project-driven book; that is, the majority of the poems were about cephalopods, the class to which octopus, squid, and cuttlefish belong. There’s something very centering about having such an extreme focus for so many years, and even the poems in the book that weren’t directly about cephalopods still found their way into the book through a kind of kinship—such as the one poem that takes place on a beach in Venice, in which I imagined an octopus washed up on the shore, completely out of frame and not mentioned in the poem at all, obvious to no one but me.

But I put pressure on myself to make a discernible break from octopuses in the next book, without knowing quite how I’d be moving forward with my work. After working without a particular agenda for a while, I began to look at the post-Octopus poems that were accumulating, and realized that there were themes from the previous book that I wasn’t quite ready to let go of. Specifically, cephalopods are masters of camouflage, able to change the color and texture of their skins, mold their bodies into extreme shapes, and some species are even capable of emitting light from their skin. Even though I’d moved on from octopuses, I found that I was still interested in exploring illusion and duplicity in my work. This led me to the idea that the next book, which would eventually become Real Phonies and Genuine Fakes, would focus on these ideas, though subject matter as diverse as drag, forgery, plagiarism, magic, taxidermy, and so on.

This collection, much like your previous collection The Octopus Game, seems to focus on obsessions and curiosities and strange occurrences seeped in a hyperrealism instead of becoming too dreamy/surreal/abstract. Do you find your writing is most generative when focused on one particular historical/cultural topic or interest?

I think it is, but finding that focus is very organic. It’s often a case of looking at a poem or a group of poems and realizing (or having someone else point out) that I’m not done writing about a certain topic or concept—the fact that the poem or poems might be finished doesn’t mean the idea is finished with me yet. And the more time I spend with an obsession, the broader and more flexible it becomes. In the case of Real Phonies, I was surprised to discover how the idea of “phoniness” applied to my own history of mental illness, and “performing wellness”—a phrase I first encountered while reading Sejal A. Shah’s terrific essay “Even If You Can’t See It: Invisible Disability and Neurodiversity.” Watching an obsession evolve is one of the most joyful parts of my writing process.

In this collection, you feature Dolly Parton, David Bowie, Bruce Wayne, Marlene Dietrich, Duckie Dale, and more. Even a Bjork epigraph. How did pop culture shape/influence your writing of this collection?

When I was working on my first book, I think I had an aversion (which was really just an insecurity) to putting pop culture in my poems. There was an anxiety—strengthened by certain elder poets I’d talked to—that references to pop culture would make the poems seem dated and/or trivial. And of course, that attitude has its basis in internalized classism, racism, etc. But when I was working on The Octopus Game, I knew I wanted to include poems about cephalopods in film; I was also reading A. Van Jordan for the first time around then, and I loved how he was using movies as both subject matter and form in his work. So the joy and satisfaction I found in writing poems about Goodfellas, Oldboy, and Ed Wood’s Bride of the Atom/Bride of the Monster showed me that I didn’t need to hide all the ways that pop culture—that is to say, culture—excites and inspires me. By the time I was working on Real Phonies, I was fully prepared to dig into pop culture any way my curiosity took me, fork and knife in hand.

This collection feels very vintage Middle America to me -- thrifting in the desert on the way to Vegas or Hollywood. Having a cigarette on Route 66. Lost in both time and space. Do you see this as a nostalgic / time capsule collection?

You know, I can’t say that I do, although I appreciate knowing that reading is present. I don’t see the collection as nostalgic, in that I hope it’s looking at the past in a way that creates a productive discomfort, rather than wistfulness. And I think of time capsules as highly curated objects assembled to reinforce a specific narrative, and I hope that the collection is a bit more disjunctive in that respect. But I’d agree that the collection is interested in the idea of America, specifically in how self-deception and selective memory are crucial aspects of Americanness. The poem “Notes on the Village of Liars” is an example of this, especially in the line “Everyone is the mayor. No one is the executioner.” White, middle-class America (of which I am inextricably a part) desperately depends upon the illusion of its own innocence, on ignoring its complicity with the violence that has founded and continues to power this country.

I'm obsessed with your sequence The Stereoscopic Man. They're so brief and concise and inventive. Can you talk about how this sequence/section came to be? Did you first see it as its own project? Did any stereoscopic drafts not make the cut?

I’m so glad you enjoy the sequence! I have a lot of affection for it, because it felt like such a departure for me while I was writing it.

I think I always saw “The Stereoscopic Man” as a sequence necessary to Real Phonies, rather than a stand-alone project. I’d wanted to work optical illusions into the book, especially after I read Eyes, Lies, and Illusions: The Art of Deception, which examines the use of optical illusions in art history. I think there may have been one or two sections that were cut, or two sections that were trimmed and combined into one, but a lot of what made it into to book was how I’d drafted it.

I talk about the origins of the poem in a recent interview with Rebecca Morgan Frank in the Adroit Journal:

I’ve been a fan of the Belgian surrealist painter René Magritte for a long time—his oeuvre is a treasure trove of visual oddities and interrogations of reality very in keeping with Real Phonies. In 2013, I saw a Magritte show at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, where I became fixated on his 1927 painting “Portrait of Paul Nougé” (Nougé was a poet in Magritte’s circle). It’s a double image of Nougé in owlish glasses and tuxedo, in which he appears to be opening a fragment of a door for himself. There was something about the stiff formality of the Nougés in this otherworldly context that made me want to write a poem that takes on their paradoxical nature: a single entity that is also twofold.

I realized that the oddness of the character I had in mind was going to demand something formally different from anything I’d ever written before—hence the “stereoscopic” form of the poems on the page in two short columns of about identical width.

But I recently recognized that my attraction to the Nougé portrait may have had deeper origins than I was originally aware of. When I was about five or six, I was diagnosed with a lazy eye, and I had to go to an optician’s office every couple of weeks for vision therapy to correct it. A lot of the exercises involved playing games and solving puzzles, but looking at pictures through a stereoscopic viewer was also involved. So for all I know, the painting may have activated some kind of unconscious affinity for me, which is why I couldn’t get it out of my head!

Your debut was released in 2010 with a follow-up in 2015 and your new book in 2022. Do you write a great deal more than what makes it into the manuscript(s), or do you consider yourself more of a slow/fine-tuning/tinkering poet? I asked a similar question to your partner Brian Barker in 2019 and he said, "I guess I’m obsessive and meticulous, as I think every poet and artist should be. But I’m also just a slow writer. I don’t like willing poems into the world. They come when they are ready to come; they sink their teeth into me when they are ready to bite."

My poems come out in so many different ways! There are definitely a number of them that are begun and ultimately don’t go anywhere, or don’t rise above the ordinary when they’re finished, but then there are the ones that will take me months or years to complete while I’m futzing with them. So I’d say I’m a combination of messy and meticulous.

Despite assuming another book might not be out until 2025 or 2027, can I ask what you are currently working on?

Ach, how dare you make me think about those years with such specificity! Right now, I’m mainly working on a collection of memoir essays that take on subjects like the early deaths of my parents (they both died from cancer in their 40s), my relationship with my younger brother, my queerness, and my ancestor Thomas Beer, who was a closeted gay man and popular writer during the 1920s. But the poems keep coming as well—I find myself wanting to write ones that are more celebratory, but also ones that are angrier, too. You could say I’m in a messy stage with them right now.

from The Octopus Game

You often masterfully toe the line between the strange/weird/humorous and the tender/gentle/emotional. Can you talk a bit about humor vs. heart?

I don’t know that I can separate one from the other. For me, humor can be just as much a form of vulnerability as tenderness is. To try and make someone laugh is a kind of invitation, to ask them join you in recognizing the absurdity, silliness, and even the pain of the world. But it also reveals something very private about who you are: sharing what makes you laugh can be just as intimate as sharing what turns you on.

Outside of your own art and writing, what albums/artists/plays/films have captivated you in recent months?

Everything Everywhere All at Once was so playful and sincere—it was one of those movies that reminds me about what a miraculous art form filmmaking is. I even got to see it in a theater (an increasingly rare event for me in Covid times) and it was the perfect film—in all its big, hilarious, heartfeltness—to just wash over me and make me feel like I’m dissolving into the screen. And because I’ve been digging through a cache of cassette tapes from high school, I’ve reconnected with The Wonder Stuff’s 1991 album Never Loved Elvis. It makes me want to run around my backyard, sticking my arms out and pretending that I’m an airplane. And I’m in the middle of reading Fat and Queer: An Anthology of Queer & Trans Bodies & Lives, and I’m truly blown away by how much care the editors (Bruce Owens Grimm, Miguel M. Morales, and Tiff Joshua TJ Ferentini) have taken to provide such varied and nuanced perspectives on the subject matter(s). This is an anthology anyone with a body should read.

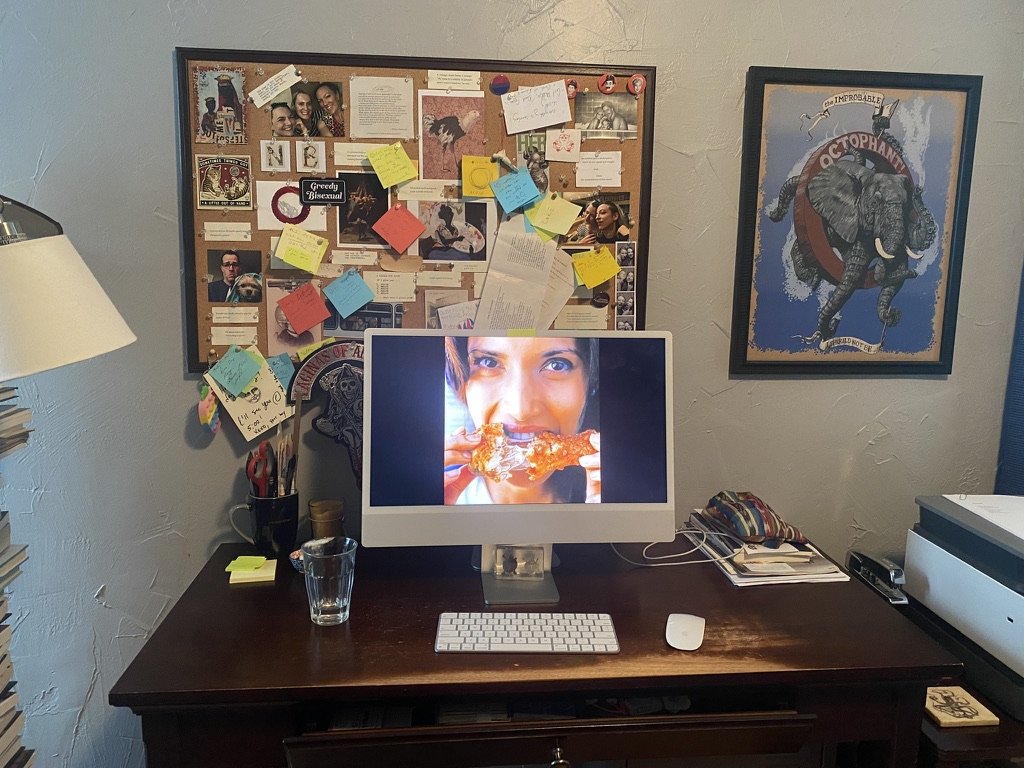

If you can, provide a photo of your workspace. What are some essentials while you create?

My essentials basically boil down to quiet and proximity to a window (and, as the photo reflects, the occasional screensaver featuring Padma Lakshmi). Sometimes I wish I were a little more high maintenance, so I could least have an excuse when I’m shirking: “I can’t finish this sonnet until I find my art deco cigarette holder!”

For this ongoing author interview series, I'm asking for everyone to present a writing prompt. It can be as abstract or as concrete as you choose.

Write a poem in which the speaker describes a memory in the first half, and then interrogates, changes, corrects, or outright negates their own version of that memory in the second half. William Matthews’ “Cheap Seats, the Cincinnati Gardens, Professional Basketball, 1959” is an excellent model for this.

In closing, do you have any advice for early writers? Or rather, what's something you would have liked to have known when you first started taking your writing seriously?

Try to examine your own beliefs about what you “can’t” write poetry about, or things you might think of writing about but don’t because you’re sure that they won’t interest anyone—that they’re not “universal” or “relatable.” The more early writers I work with, the more I’m convinced that this self-suppression is a major enemy when it comes to developing one’s art. Despite the fact that my first book is about the death of my father (and that I know now that I’ll probably be writing my parents’ deaths for the rest of my life), I’d convinced myself in the years beforehand that writing about my dead parents was too familiar—a cheap, sentimental bid for the reader’s sympathy. And of course, I can now see that as a way of avoiding what I absolutely had to write about. It’s so, so easy to rationalize not writing about the things that actually make you who you are, because those are the fucking scariest things to take on. And the status quo always has a vested interest in discouraging people from marginalized communities and people with traumatic experiences from making their experiences visible in ways that don’t serve those in power. So when you hear that voice inside you saying “You can’t write about this,” ask yourself: who’s really speaking here? Who has tried to make you believe that your experiences don’t deserve attention?

Any final thoughts / words of wisdom / shout-outs? Thank you!

Ortiz brand anchovies paired with pickled red onions are delicious! And thank YOU!