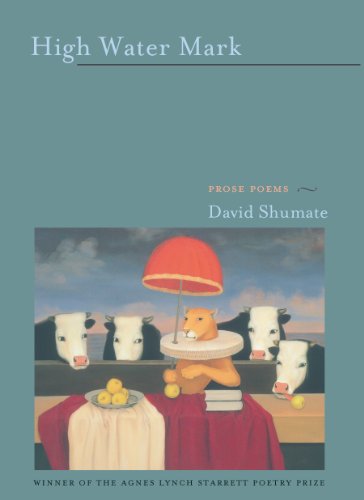

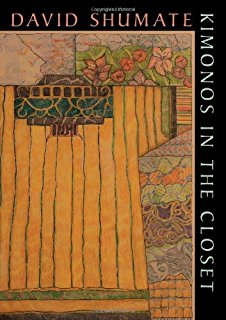

In a 2016 interview with Geosi Reads, prose poet and professor David Shumate said, "Like most poets, I write in the solitary confines of my study as an exercise in dreaming while awake." That quote became embedded in my skull, as I later wrote it out on a Post-It to keep on my computer. The author of three books of prose poems (all featured on my 2017 year-end list and all released through Pitt Poetry Series), Shumate manages to properly blend the magical with the spiritual with the religious with the absurd. His stories can fly seamlessly in any direction, often concluded with harmony, humor, and insight. Nothing is out of range of being made possible. To read Shumate is, like he says, dreaming while awake. I spoke with the Midwestern author who has been living in Indiana since the 70s, and asked him about his recent retirement from Marian University, his advice to his students, and the three manuscripts he has in the works.

via The Floating Bridge

To get the ball rolling, when did you first develop a fascination for the prose poem?

I remember coming across Robert Bly’s translation of Lorca and Jimenez’s work, and in that fine book there were a half dozen or so prose poems by Juan Ramon Jimenez. I was intrigued by their blend of lyricism and narrative. Later a friend gave me a copy of Bly’s Morning Glories, a collection of prose poems, and I found that equally liberating. I noticed there was a thin frontier between narrative prose and lyrical poetry that felt ripe for exploration. Later I read Jim Harrison’s Letters to Yesenin and some of Tomas Transtromer’s prose poems, both of which opened up new dimensions for me.

It is a craft/discipline that you have been mastering for over a decade. Do you see yourself ever growing tired of this style?

The form still feels natural and vibrant to me. But I do write in other forms as well—lineated poetry, fiction, some essays—but most of what I have published so far is prose poetry. I find the act of balancing between the narrative and the lyrical, the humorous and the tragic, the mystical and the mundane, still suits me well.

What are you currently working on?

I am working on three manuscripts—a collection of prose poems, a collection of line-break poems, and a longer piece of fiction. I generally start my writing day with poetry and then move later to fiction. I am an ardent believer in writing early and regularly. If I stay away from writing even for a few short days, I find I have to reteach myself how to open some of the doors of the imagination, a skill that otherwise, with regular writing, comes naturally.

Outside of your own works, what other authors/books have inspired/influence you over the years?

I have been a longtime fan of Jim Harrison’s work. I find his fiction and his poetry to be vital and unabashedly honest. I was influenced early on by Richard Brautigan, too. And I owe a great debt to the Colombian novelist, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, whom I consider the be one of the greatest writers of our age, if not all time.

But I found myself coming alive to poetry when I first encountered the Chinese poets of the Tang Dynasty and other periods in the translations of Kenneth Rexroth and Arthur Waley. They liberated me from the constraints of Western poetry.

Prior to your recent retirement, you were a professor at Marian (and Butler), is that right? Were you born and raised in Indiana as well? (I graduated from Butler in '10)

I taught at Marian University for about thirty years, and I have been a lecturer in the Butler University MFA program for about five years, but I was born in Iowa City and spent most of my youth in Kansas. I’ve lived in Indiana since the mid-seventies. I’ve traveled quite widely, and much of my writing has been informed by that, but so much of what I write is deeply rooted in Midwestern landscapes and sensibilities.

Did you find it difficult to maintain your own poetic voice while teaching and working directly with so many students with different styles?

I always find it intriguing to see how my students, most of whom are younger than I am, approach the stuff of poetry. They are growing up in a world that is much changed compared to the one I encountered in my youth. And so naturally their insights and expressions are different. But my poetic voice, my way of approaching a topic and rendering it in poetry, is informed by my years of experience on this earth and therefore, at this point, fairly solidly established.

How has retirement been treating you? What's the rest of the year looking like?

I am enjoying the increased writing time retirement has afforded me, not only the greater amount of time but the quality of it. I no longer feel the outside world pressing in on me as much when I write, whispering that I need to get up and attend to this or that. I still teach occasionally at Butler and in other venues as well. Last August I taught a weeklong seminar at the Chautauqua Institution in Western New York and enjoyed it very much.

For this ongoing author interview series, I'm asking for everyone to present a writing prompt. It can be one that you craft out of thin air, it can be one you created a while back, or it can be one you adore from an outside source that was passed down to you.

I’m afraid I don’t work very well with prompts. In my teaching, I emphasize that there are a few fundamentals every poet, every writer, must know and practice to be effective—1) the stuff of poetry (or fiction) is everywhere, and 2) pay attention.

If a writer understands that our everyday experience is infused with the poetic, then each of those observations serves to prompt us, to prod us into writing. The second essential element—pay attention—is a reminder that if we are not attentive, receptive to what is going on around us, we are squandering our greatest resource as a writer. So, the best prompt, I think, is that lifelong prompt—pay attention to the everyday, seemingly even mundane facets of your life. That is where the gold is.

Do you have any advice for authors/poets working on their craft?

Much of what I mentioned in my answer to the previous question also stands as general advice to writers. But, also, write regularly. And in the early stages of writing a poem, allow yourself to be playful, humorous, redundant, mundane, predictable and flat out wrong. And in the process, you will find yourself stumbling upon the unexpected, the liberating.

I remember once hearing Michael Ondaatje quote the old Chinese adage regarding the creative process—“Follow the brush.” That has stuck with me. This acknowledges that it is not the intellect that guides us to the treasure. It is that subtler, intuitive realm of the individual that nudges us along to the unexpected, to the revelatory. If we impose our will too strongly on the poem, we will usually end up only with the expected, the predictable. If we “follow the brush,” or cede control of the poem to the more intuitive facet of our writing self, feeling our way through a poem in the early stages rather than only thinking our way through it, we will pass over the frontier of the ordinary and find ourselves in the territory of myth.

via poets.org